(Original Artwork Above by Howard Terpning)

Cleopatra - The Backstory begins here

The

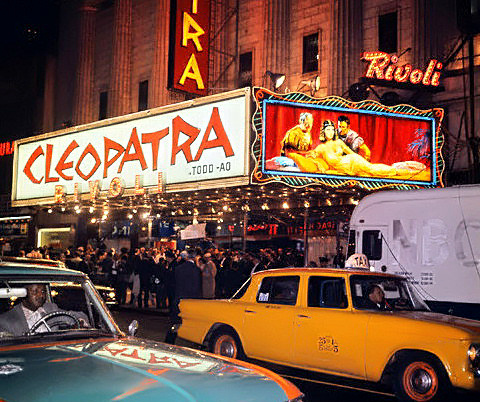

truth was that everyone had come to the premier of Cleopatra to see the train wreck for themselves. Everyone knew that it was an extraordinarily botched production which had cost the studio an unheard of $44 million in 1963. Hollywood’s previous all-time record setter, Ben-Hur had cost a mere $15 million just four years earlier, chariot race and all. Cleopatra had nearly gutted Twentieth Century Fox. It had taken two Directors, two separate casts, two Fox regimes, and two and half years of stop-start filmmaking in England, Italy, Egypt and Spain to get it to the screen.

Never before had celebrity scandal been pushed so far into the global consciousness, with Richard and Liz even pre-empting John Glenn’s orbiting Earth on the front pages of tabloids around the world. They were denounced on the U.S. Senate floor and even an ‘open letter’ published in the Vatican Newspaper chastised Taylor for ‘erotic vagrancy’. Liz had already been four times a bride, once a widow, and once a home wrecker when she signed on for the role of Cleopatra. It was in this role that she truly transcended the label of ‘movie star’ and became once and for all, Elizabeth Taylor, the protagonist in an extra-vocational melodrama of star crossed romance, exquisite jewelry and periodic hospitalizations.

“It was probably the most chaotic time of my life. That hasn’t changed”, said Liz, who has seldom discussed the Cleopatra experience publicly. “What with le scandal, the Vatican banning me, people making threats on my life, falling madly in love… It was fun and dark with oceans of tears, but some good times too.”

For old Hollywood, Cleopatra represented the moment when the jig was up. No longer would anyone buy the studio system’s sanitized, pre-packaged lives of the stars, nor would the stars and their agents bow in obeisance to the aging moguls who’d founded Hollywood. It was the moment when every shmoe on the street became an industry insider and knew all about Liz’s deal ($1 million against ten percent of the gross), aware that a given film was x million dollars over budget and needed to earn back y million just to break even. Heaven’s Gate, Ishtar, Waterworld, the modern narrative of ‘the troubled production’ began right here, though none of these films would come close to matching Cleopatra for sheer anarchy, overreach, and bad karma. It was this movie that originated the mixed blessing concept of ‘…the most expensive movie ever made…’. In strict economic terms, Cleopatra still holds the title. Variety estimated Cleopatra’s cost in 1997 dollars to be $300 million, a full $100million more than Titanic.

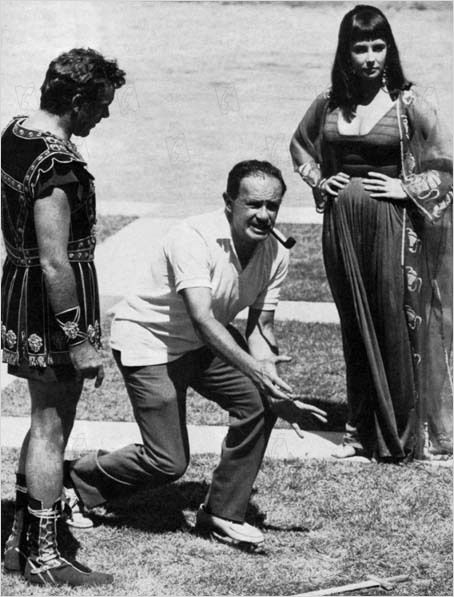

Director Joseph L. Mankiewicz called Cleopatra, ‘…the toughest three pictures I ever made…’ and his epitaph for the film was that it was ‘…conceived in a state of emergency, shot in confusion, and wound up in a state of blind panic..’ which has become one of filmdom’s most famous quotes. Even now the movie’s survivors talk of its making almost as if they’re discussing a paranormal experience. ‘There was a certain madness to it all’ said Hume Cronyn who played Sosigenes, Cleopatra’s scholarly advisor. ‘It wasn’t anything as clear as Richard Burton is moving out on his wife and Elizabeth is leaving Eddie Fisher. It was much more complicated, many more levels than that, Paparazzi hiding in trees. We were weeks behind schedule. Hanky panky in this corner and that. There were wheels within wheels within wheels. God, it was a very messy situation.’

Although it turned up making a small profit and winning modest critical acclaim, Cleopatra had some very grim aftereffects on many of it’s principals. Director Mankiewicz would never again attain the heights of his late forties to late fifties peak during which he pulled off the still unmatched feat of winning four Oscars in two years, for writing and directing A Letter To Three Wives (1949) and All About Eve (1950). ‘Cleopatra affected him the rest of his life’ said his widow Rosemary, who worked as his assistant on the film. ‘It made him more sensitive to the other blows that would come along’. Mankiewicz would make only three more feature films, including his last which became a minor jewel Sleuth in 1972. He then spent his final 21 years disillusioned and idle, ‘finding reasons not to work’ according to his son Tom.

In Cleopatra’s aftermath Richard and Elizabeth would marry each other twice and give just one more really excellent performance together. Mike Nichols Who’s Afraid f Virginia Woolf? (1966). The remaining films made together The V.I.P.s, The Sandpiper, The Taming Of The Shrew, Dr. Faustus, The Comedians, Boom!, Divorce His, Divorce Hers, were drink sodden exhibitions of international jet set filmmaking and more about the deal than the performance.

Fox was not a well run operation in the late 50s. All of the studios were suffering from the rise of television and the court ordered dissolution of the studio system. Spyros Skouras was the president of 20th Century Fox during Cleopatra filming and was having a particularly rough time of it. An internal report published in 1962 showed a four year loss of about $61 million. ‘We were the only people who could put John Wayne, Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe in the movies and not have them do any business’ said Jack Brodsky, Fox publicist during the Cleopatra years.

One reason for Fox’s weak performance was the 1956 departure of it’s founder and resident genius, chief of production Darryl Zanuck, who had burned out after 23 years on the job and quit to become an independent producer. Zanuck’s replacement was Buddy Adler who proved to be a very ineffective executive. As long as Zanuck had been in place, the New York based Skouras, a Greek immigrant who had worked his way up from owning a single movie theater in St. Louis and had kept his distance from Los Angeles and the actual film making process. With Adler as chief of production Skouras felt no such restraint and began to meddle heavily in the production side of the business.

Skouras was no creative genius but had made one important strategic decision that temporarily “saved” the industry from television, he had kicked off the wide-screen era by making The Robe a 1953 biblical epic starring Richard Burton and the studio’s new CinemaScope technology. The film’s success ($17 million on a budget of $5 million) soon made Skouras a Hollywood hero and every studio was rushing out to make their own sand swept period epics in rival wide screen format such as WarnerScope, TechniScope and VistaVision.

By the time the studio was trying to get Cleopatra off the ground the infatuation with CinemaScope was on the wane and the budget minded Adler envisioned a modest backlot production of Cleopatra costing perhaps a million or even two million dollars starring a Fox contract player like Joan Collins, Joanne Woodward or even Suzy Parker. When Taylor was suggested Skouras didn’t want her because ‘she’ll be too much trouble’.

Everyone in the movie business loved Producer Walter Wanger. Walter was Dartmouth educated, well spoken and strongly contrasted by most movie executives who shouted at practically everyone. Walter developed a reputation as an intellectual and a socially conscious movie executive who produced provocative message movies and glittering romantic melodramas. Walter was strongly influenced by European films, and made many productions geared towards international markets and for years his dream had been to do Cleopatra as an epic sized motion picture.

That year Walter Wanger was not in the best position to do a deal. After a couple of decades as one of Hollywood’s most successful independent producers, credited with such films as Queen Christina with Greta Garbo and John Ford’s Stagecoach he’d fallen on a hitless period and discovered his wife, the beautiful actress Joan Bennett was having a torrid affair with her agent Jennings Lang of MCA. On Dec. 13, 1951 Walter followed his wife Joan and found her meeting with Jennings Lang in the MCA parking lot. Walter quickly walked up to Jennings, pulled out a gun and shot Jennings right in the crotch.

Walter was sentenced to serve a mere four month stay at a Southern California ‘Honor Farm’ in 1952. The sentence spoke volumes about how well liked he was and by those that contributed to his ‘defense fund’. Names like Darryl F. Zanuck, Walt Disney, Harry and Jack Warner, and Samuel Goldwyn. The powers of Hollywood came down strongly on Walter’s side as I suspect studio management believed ‘the only good agent, was a dead agent’, although that’s pure speculation on my part. (Photographs Here)

By 1958 Walter’s comeback was in full swing having recently produced Don Siegel’s SciFi thriller Invasion Of The Body Snatchers and Robert Wise’s I Want To Live! winning Susan Hayward an Academy Award for Best Actress. Once again Walter’s thoughts turned to his dream project Cleopatra. On Sept. 30, 1958 Walter took his first meeting with Spyros Skouras (President of 20th Century Fox) to discuss Cleopatra. Spyros had a much more modest view of the project than the epic proposed by Walter.

On June 19, 1959 Walter received his first preliminary operating budget for Cleopatra detailing 64 days of shooting at a cost not to exceed $2,955,700, exclusive of cast and director salaries. A very modest budget by Hollywood standards for an epic production. That decade had produced one record setting mega production after another starting with Mervyn LeRoy’s Quo Vadis (1951 - $7 million) followed by Richard Fleischer’s Jules Verne fantasy 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954 - $9 million), Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956 - $13 million) and of course William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959 - $ 15 million).

By late that summer a reputable British writer named Nigel Balchin had been hired to put together a script, a $5 million budget was deemed acceptable and the names of Taylor, Audrey Hepburn, Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida and Susan Hayward were being discussed for the title role. On Sept. 1 Walter Wanger made his first formal overture to Elizabeth who was in London filming Suddenly Last Summer with Joseph Mankiewicz. Over the telephone she demanded – half jokingly – a million dollars, something no actress had ever been paid for a single movie.

Finally, on October 15 Fox staged a photo opportunity for the press at which Elizabeth pretended to sign her million dollar contract. The wire services sent out the photo to newspapers across the country and for the first time on front pages everywhere was a woman getting a million dollars for her performance. Walter Wanger’s idea of having Elizabeth Taylor portray Cleopatra now belonged to the world.

Getting Nowhere: New York, Los Angeles, London 1959-60

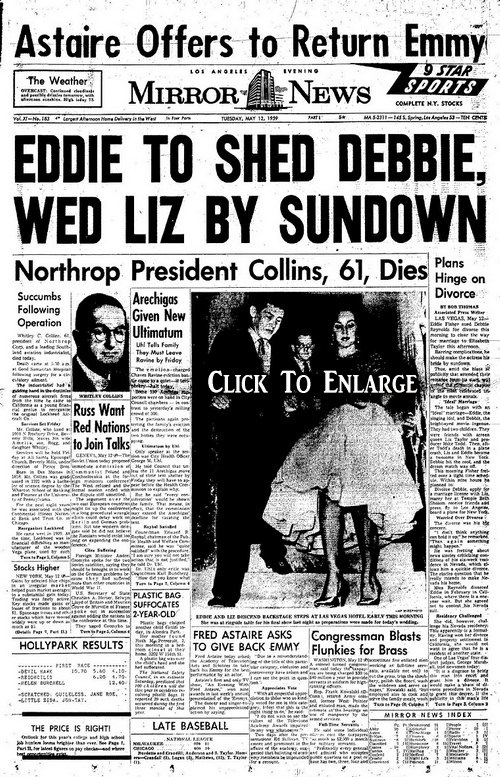

‘Gentlemen: You are wasting your money on Liz Taylor. Nobody wants to see her after the way she treated sweet little Debbie Reynolds. Everyone loves Debbie. She is what teenagers call a doll. Ginger Rogers is still popular, but Liz is not liked anymore. I heard a group of teenagers talking about Liz. They said ‘…she is a stinker…’. They’re right.’

by a woman in Beaumont Calif. Oct. 1959

It is the wisdom of those who consider themselves experts on the subject that Mike Todd, the producer-showman behind Around The World In Eighty Days was ‘the love of Elizabeth Taylor’s life’. Although less than six months after Todd died in a plane crash outside Albuquerque in March 1958 – leaving the 26 yr. old Taylor alone with an enfant daughter, and the two sons she’d had with her second husband, Michael Wilding – she was seen stepping out with her late husband’s friend and protégé, Eddie Fisher. Eddie was a pompadoured, haimish 30yr. old pop star idol most famous for his shrewdly publicized union with Miss Debbie Reynolds. Together, Eddie and Debbie had two children and were known far and wide as ‘America’s sweethearts’. By the time Elizabeth and Eddie were married to each other in Las Vegas in May of 1959 the public goodwill both had built up vanished and they were the target of paparazzi surveillance and very questionable morals.

Spyros Skouras’s intuition that Taylor would be ‘trouble’ wasn’t entirely unfounded, in that she had a predisposition to illness, and alarmed moralists practically everywhere. Then again she had soldiered on through Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, the film she was making when husband Todd died, fulfilled her obligation to Butterfield 8, the last film she owed to MGM under her contract, and even delivered a first rate performance in Suddendly Last Summer.

Reaching over Wanger’s head Skouras tapped an old friend, Rouben Mamoulian to be Cleopatra’s director. The 61 yr. old Mamoulian was a gifted visualist, was accustomed to policing large groups of people, and had directed the original Broadway productions of Porgy and Bess, Oklahoma!, and Carousel, as well as the films Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Becky Sharp and Silk Stockings. But he had a reputation as a temperamental man, and his film making skills were rusty. The screen writer Nunnally Johnson (The Grapes Of Wrath), whom Fox had hired to write additional dialogue for Balchin’s screenplay was skeptical. ‘I bet Walter Wanger that Mamoulian would never go to bat’, Johnson wrote to his friend Groucho Marx, ‘All he wants to do is “prepare”. A hell of a preparer. Tests, wardrobe, hair, toenails…, but if you make him start the picture, he will never forgive you to his dying day. This chap is a natural born martyr’.

Late in 1959 the Fox management committed its first major mistake. Someone decided, besides obvious observable evidence to the contrary, that chilly overcast England was an ideal place to shoot a sun-drenched Egyptian-Roman epic. The decision was of course money driven as the British government had offered very generous subsidies to foreign productions that would hire a certain percentage of British crew on the production.

Adler died of cancer the following July and his death created even more of a power vacuum at the studio, but the movie’s chief detractor at Fox was out of the way. On July 28, 1960, Elizabeth finally signed a real contract with the studio. The film was not to be shot in CinemaScope but in Todd-AO, a rival wide screen process developed by Mike Todd, which meant that Elizabeth as Mike Todd’s heir, would receive additional royalties. It was announced that Peter Finch would play Caesar and Stephen Boyd, Charlton Heston’s co-star in Ben-Hur would play Antony. At the Pinewood Studios, located just outside London, John DeCuir, one of the best art directors in the business, began construction on a gorgeous $600,000 Alexandria set covering 20+ acres featuring a bevy of palm trees flown in from Los Angeles and four 52ft. high sphinxes.

Right from the start, Mamoulian’s Cleopatra was in chaos. The first day of shooting, September 28, saw two work stoppages by the movie’s British hairdressers, who took issue with Taylor’s specially imported American hairstylist, Sidney Guilaroff. Only after several weeks of negotiations by Walter Wanger was a very fragile truce arranged. Guilaroff would style Elizabeth’s hair at her double penthouse suite in the Dorchester, but would not set foot in Pinewood.

Not that Elizabeth’s presence at Pinewood ever became much of an issue. She called in sick on the third day of shooting saying she had a cold. The cold grew into a lingering fever and for the next few weeks she remained sequestered in her double suite, attended to by her husband Eddie Fisher and several doctors, including Lord Evans, Queen Elizabeth’s personal physician.

Physically and spiritually Mr. and Mrs. Fisher were not a healthy couple. Eddie missed his singing career which he had largely given up to be with Elizabeth and he knew the $150,000 he was being paid by Fox for rather vague junior producer duties was really for being Elizabeth’s professional caretaker. Furthermore he was strung out on methamphetamines, having gotten hooked in his grueling touring days on “pep” shots administered by Max Jacobson, the notorious “Doctor Feelgood” who provided the same services to John F. Kennedy.

Elizabeth was in a continual depression because of her ill health, residual grief over the death of Mike Todd, the rather grim English weather, and her own correct intuition that she was squandering her own star power to a doomed, disorganized project. In response she took to drinking and taking pain killers and sedatives (never a good combination). “She could take an enormous amount of drugs” Fisher told Brad Geagley, a senior producer at Walt Disney in an unpublished 1991 interview for a never completed book concerning Cleopatra. “She’s written up in medical journals somewhere – that’s what she told me and I believe her”.

While Elizabeth spent the autumn going between the Dorchester Hotel and the London Clinic where she was variously diagnosed with a virus, an abscessed tooth, a bacterial infection known as Malta Fever, Mamoulian was having his own troubles. Balchin’s script remained unsatisfactory to him and in the rare moments when the sun actually shown, the illusion of Egypt was shattered by the steam visibly emanating from the actors’ and horses’ mouths.

Production finally ground to a complete halt on November 18, when there was simply no more Mamoulian could do without the physical presence of Elizabeth and an improved script. The plan was for shooting to resume in January by which time Elizabeth would presumably be well and Nunnally Johnson would have finished polishing the script.

Back in New York, Skouras sent a copy of the current shooting script to Joseph Mankiewicz who had made his two Oscar winning pictures for Fox and asked him for a honest and frank critique. Mankiewicz was brutal in his frankness, “Cleopatra, as written, is a strange frustrating mixture of an American soap-opera virgin and a hysterical Slavic vamp of the type Nazimova used to play…”.

On January 18, 1961 with production resumed but still moving at a glacial pace, Mamoulian, now bitter and frustrated, cabled his resignation to Skouras. He left behind about 10 minutes of footage, none of it featuring Elizabeth Taylor and a loss of $7 million.Near Death moment, London 1960-61

“I began to look at my life and I saw a tough situation. In the hospital all the time – I mean I became a nurse. I was giving her injections of Demerol. I didn’t want the doctors to come. I felt sorry for the doctors. I did it for two nights and whooo-ee… After two nights I said this is crazy. I actually faked appendicitis to get away”.

A couple of days after Spyros Skouras accepted Mamoulian’s resignation, a desperate voice broke through the static on Hume Cronyn’s phone in the Bahamas, where he owned a remote island with his wife Jessica Tandy. “Hume?” said the voice, “where the hell is Joe?”.

It was Charles Feldman, Joe Mankiewicz’s Hollywood agent. Mankiewicz was staying with Hume and Jessica preparing the screenplay for Justine, his planned follow-up to Suddendly Last Summer. Feldman told Mankiewicz that Skouras was offering the moon if he would come and rescue Cleopatra. The director was skeptical but that didn’t stop him from immediately flying to New York to meet with Skouras at The Colony for lunch.

“Spyros”, he said, “why would I want to make Cleopatra? I wouldn’t even go see Cleopatra”.

Gifted as he was, Mankiewicz seemed the last person qualified (or inclined) to helm a big budget epic full of raw spectacle. “His movies were dialogue based and staged like plays, like All About Eve, where most of the action, where there is action, is people coming down stairs or going in and out of doors”, says Chris Mankiewicz, the director’s older son, who took off from college to work on Cleopatra. Skouras recognized the elder Mankiewicz was a great writer and very skilled diva wrangler, having finessed the egos of Elizabeth Taylor and Katherine Hepburn on Suddendly Last Summer and Bette Davis on All About Eve.

Mankiewicz agreed to take over the project when Skouras made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. Fox would not only place him on salary, but would also pay $3 million for Figaro, the production company he co-owned with NBC. For a 51 yr. old man whose glorious career had never quite made him rich, the prospect of being an overnight millionaire was irresistible. “He was seduced by the opportunity” says Chris Mankiewicz. He never saw a penny from All About Eve. Suddenly for once in his life, they were all coming to him.

For a fleeting moment in time Cleopatra seemed to be in good sane competent hands. Mankiewicz, citing as his inspiration Shaw, Shakespeare and Plutarch, set about creating a totally new script. He enlisted two writers to help him, novelist Lawrence Durrell (whose Alexandria Quartet was the basis for Mankiewicz’s Justine script) and screenwriter Sidney Buchman (Mr. Smith Goes To Washington). Walter Wanger was elated with Mankiewicz’s “modern psychiatrically rooted concept of the film”, and thought at last he was getting the upscale Cleopatra he’d always dreamed of.

Ahh… but alas poor yorick, it was during this time that Elizabeth Taylor suffered what probably qualifies as her nearest near-death experience up until that time. Late in February she returned to London from a vacation on the Continent with what her doctors would described as “Asian Flu”, caught while rushing back to attend her suddenly “appendicitis” stricken husband. By March, the Asian Flu, or whatever it was, had complicated itself into double pneumonia, and Elizabeth was sedated and prone in an oxygen tent at the Dorchester. On the night of March 4, 1961, she fell comatose. She was rushed once more to the London clinic, Eddie Fisher at her side screaming “Let her alone! Let her alone!” as paparazzi leaned in to get photographs of her as she lay unconscious. The persistence of the Fleet Street paparazzi ensured that within hours there was an international deathwatch in place, some papers already reporting that Elizabeth had died.

“I was pronounced dead four times” said Elizabeth, “Once I didn’t breath for five minutes, which must be some kind of record”. Doctors performed an emergency tracheotomy to alleviate congestion in her bronchial passages. The operation saved her life and by the end of the month she was back home with husband Eddie Fisher in Los Angeles, recovering. Several months later she underwent plastic surgery to conceal the scar the incision had made at the base of her throat, but it was not an entirely successful operation as you can see the scar in the finished film.

Whacky as the whole episode was, it had two beneficial effects. First it bought Mankiewicz six months to get his Cleopatra together while Elizabeth recovered. Second, Elizabeth’s public image was transformed almost overnight from home wrecking tart to heartstring pulling survivor. The London Clinic received truckloads of flowers and thousands of sympathetic fan mail letters and cards, even a get-well card from Debbie Reynolds. “I had the chance to read my own obituaries” said Elizabeth, “they were the best reviews I’d ever gotten”. During her recovery she received a sympathy best-actress Oscar for Butterfield 8, a movie she hated.

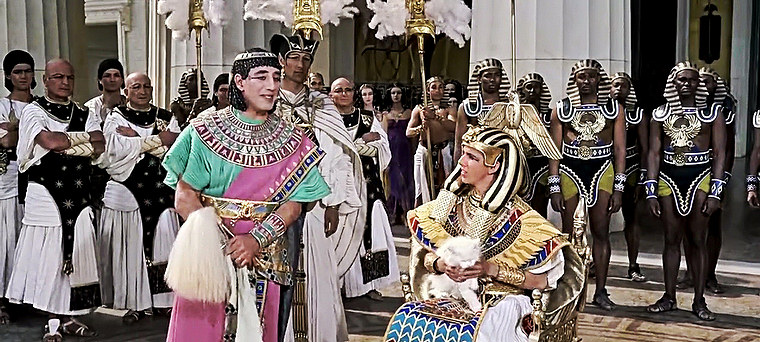

Mankiewicz decided to junk the ten minutes of footage left behind by Mamoulian and reconstruct the entire movie from scratch – only Elizabeth, Walter Wanger, and John DeCuir the art director, would carry over to the new and improved Cleopatra. To replace Peter Finch and Stephen Boyd, Mankiewicz pursued Trevor Howard and Marlon Brando. Marlon had played Mark Antony in Mankiewicz’s 1953 adaption of Julius Caesar. Neither actor was available so Mankiewicz drew a bead on Rex Harrison, whom he had directed on The Ghost and Mrs. Muir and Richard Burton who was then starring in Camelot on Broadway.

Spyros Skouras hated both choices. Rex Harrison, he said, had never made a profitable movie for Fox, and “Burton doesn’t mean a thing at the box office”. Indeed, Burton, the 36yr. old product of a dirt poor Welsh mining family, was perceived in Hollywood to be a great stage actor whose film career had never really taken off. But grudgingly, after a lot of lobbying by Mankiewicz, Skouras gave his consent. Fox bought out the remainder of Burton’s Camelot contract for $50,000 and signed the actor for $250,000, and got Rex Harrison for $200,000.

If you had to peg one of Cleopatra’s two male stars as a potential trouble maker on the set, it would have been Harrison, sometime later Walter Wanger expressed surprise that Rex had turned out to be “the good boy”. Described by several of his surviving castmastes, Harrison was known for being tetchy, difficult to work with and very condescending. Burton, by contrast, was a real charmer, adored by his peers for his erudition, basso speaking voice, Welsh-born raconteurship and sexual magnetism. Though notorious for his philandering – he had romanced such co-stars as Claire Bloom, Jean Simmons and Susan Strasberg. He had even showed up to meet Walter Wanger for the first time at New York’s ‘21’ Club with a Copacabana dancer on his arm – although he invariably returned to his wife, the dignified Sybil Burton.

One of the few people who had somehow remained oblivious to Burton’s charms, was in fact, Elizabeth Taylor. She had met him years before at a party at Stewart Granger’s house, back when she was a contract player at MGM. “He flirted like mad with me, with everyone, with any girl who was even remotely pretty”, said Elizabeth. “I thought, oh boy, I’m not gonna become a notch on his belt”.

Cleopatra in Italy

England All Over Again: Rome 1961

"It appears that the responsibility for increased cost in connection with the production falls into four categories:

(1) Elizabeth Taylor

(2) Lack of planning(3) Corruption on part of employees

(4) Friction between American and Italian heads

No effort was made at this time to review the first category, due to the danger involved".

Excerpt from a report prepared by Nathan Frankel, C.P.A., who was retained by 20th Century Fox in 1962 to determine how the studio's money was being spent on Cleopatra.

The

second go-round for Cleopatra, now relocated to Italy, was a folly of proportions nearly as epic as the finished film. Once again, the production rushed ahead without a completed script or adequate preparation, an indication of how desperately Skouras wanted to present 20th Century Fox’s board of directors with a ready-to-release film that would bring in cash and save his regime. Walter Wanger later estimated that if he and Mankiewicz had been given more time to regroup and plan, Cleopatra would have cost about $15 million. But Skouras was not at his managerial best in 1961. Elizabeth, Eddie Fisher and Mankiewicz got a sense of his addled state of mind one night when he joined them for drinks in New York. The others in the group couldn’t help but notice that Skouras was addressing Elizabeth only as “Cleopatra”.

“You don’t know my name, do you?” Elizabeth said, “and you can’t remember my name. Spyros, tell me my name!”.

“You are Cleopatra!”“You are paying me a million dollars,” Elizabeth said, “and you can’t remember my name. Spyros, tell me my name! I’ll give you half of the money back if you can tell me my name”.

“Ehh… ahh…” Skouras sputtered, “you are Cleopatra!”.By the summer of 1961 Cleopatra was practically all Fox had left, short of funds, the troubled studio had cancelled most of its other features and had pinned much of its hope on television. The latest in Fox’s series of regent studio chiefs was one Peter Levathes, a Skouras protégé who had won good notices as the head of the company’s television division.

“We decided to move the production to Rome because we thought Elizabeth would show up more” said Levathes. “The climate would be more to her liking, and she wouldn’t call in sick all the time”. At Levathes urging, Skouras granted Eddie Fisher’s request to fly in Elizabeth’s personal physician, Rex Kennamer of Beverley Hills for a fee of $25,000.

Interiors and Roman exteriors were now to be shot at Cinecittà, the massive studio complex six miles outside of central Rome. Ancient Alexandria was being reconstructed at Torre Astura, a hunting estate on the Tyrrhenian Sea owned by Prince Stefano Borghese. Some additional work, mostly battle sequences, would be filmed in the Egyptian desert.

After looking over all the thousands of files and voluminous documents left in the wake of Cleopatra, one walks away with a curious understanding of the abject terror Elizabeth inspired in very powerful men. (As Eddie Fisher would later say, “One thing I learned from Elizabeth – if you ever need anything, yell and scream for it and it will eventually show up”). Privately, Walter Wanger, Mankiewicz, Skouras, and Levathes complained about her fragility and erratic work habits, and talked about how she deserved a good telling-off. But in her presence they always lost their nerve and caved. Skouras and Levathes tried (unsuccessfully) in 1961 to sign her to a four picture deal with Fox. Walter Wanger set her up in a 14-room mansion in Rome called the Villa Papa and flew in chili from Chasen’s restaurant for her. Mankiewicz reportedly shuffled shooting schedules to accommodate her menstrual cycles. “We could only shoot Roman scenes in the Senate (which did not involve Elizabeth) when Elizabeth was having her period,” said Kenneth Haigh, who played Brutus. “She said, ‘Look, if I’m playing the most beautiful woman in the world, I want to look my best’”.

By the time the production had moved to Rome, these powerful men had an even better reason to indulge and coddle Elizabeth, even more than the usual keep-the-talent-happy ethos which permeated most productions of the time. Because of Elizabeth’s ‘near-death’ experience she had become uninsurable. If she walked off or fell ill, the movie – which was Elizabeth Taylor – would be nothing but a huge stain of red ink on the balance sheet.

Mankiewicz, between scouting locations, assembling a cast, and consulting with department heads was still not close to having a finished screenplay when shooting began on September 25. There was a mere 132 pages of script out of an eventual 327, or most of the film’s first half (“Caesar and Cleopatra”) and none of its second half (“Antony and Cleopatra”). This meant the film would have to be shot in continuity, a very costly process that would eventually result in 96 hours of raw Todd-AO negative.

Skouras insisted on moving ahead anyway, arguing that “the girl is on salary”, an allusion to Elizabeth’s renegotiated contract, which called for her to work 16 weeks beginning August 1, with a guarantee of $50,000 for every week Cleopatra ran over. Consequently, Mankiewicz would spend the remainder of the production directing day by day and writing by night, an impossibly taxing task that, said his widow, “damn near killed him”. Yet another screen writer, Ranald MacDougall (Mildred Pierce) was drafted in, but Mankiewicz still insisted on writing the actual shooting script himself.

Casting was done on the fly, a flurry of mid-September phone calls brought aboard such actors as Hume Cronyn, Martin Landau and Carroll O’Conner from America and Kenneth Haigh, Robert Stephens and Michael Horden from England. But, when the actors arrived in Rome, they discovered half-finished sets, incomplete wardrobes and a totally exhausted writer-director who hadn’t yet written their parts. Said Cronyn “I arrived the same day as Burton, September 19, 1961. Neither of us worked until after Christmas”.

“I had a 15 week contract, which was long for those days, but it wound up being almost 10 months”, said Carroll O’Conner who played Casca, a Roman senator who puts the knife in Caesar’s back. “In all that time I worked exactly 17 days”.

The hurry-up pace demanded by Skouras resulted in all manner of jaw dropping blunders that might have been avoided had there been adequate time to prepare. The beach at Torre Astura, where DeCuir’s massive replica of Alexandria was under construction, turned out to be laced with live land mines left over from the landings in WW II. A $22,000 ‘mine removal’ expenditure was added to Cleopatra’s budget. Then of course, as it turned out the set was directly adjacent to a N.A.T.O. firing range. Walter Wanger wrote in his diary “We will have to arrange our shooting schedule so the big guns are not blasting away”. Of course Italy had no facilities for processing Todd-AO film, the days rushes had to be sent all the way back to Hollywood and then back to Rome before the director could actually see them.

DeCuir’s sets were grandiose and beautiful, but because no one had kept close tabs on his work, Mankiewicz and his crew discovered too late that they were almost unmanageably big. The fake Roman Forum, (which cost $1.5 million) dwarfed the real one just up the road. So much steel tubing was required to hold it up that Cleopatra created a country wide shortage of it and affected the Italian construction business nationwide.

DeCuir’s Rome grew as 20th Century Fox began to shrink. Earlier that year, Skouras, desperate to staunch the hemorrhaging of the company’s vast resources, had engineered the sale of the studio’s 260-acre Los Angeles lot to the Aluminum Company of America for $43 million, a transaction that would come to resemble Peter Minuit’s $24 deal for Manhattan. Though the studio continued to lease 75 acres for its own use, the remaining acreage was now being developed into Century City, the gigantic office building and shopping center complex that stands just south of Beverly Hills today.

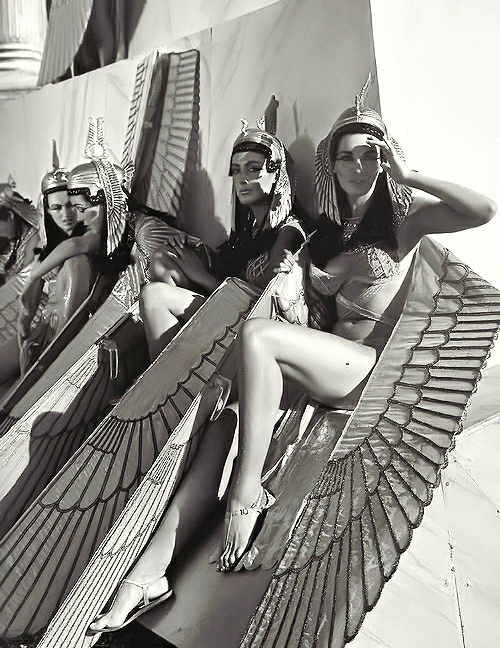

Here are just a few of her fabulous costumes.

The sheer magnitude and obvious disorganization of Cleopatra made it an easy target for anyone practiced in the art of graft – a circumstance not lost on many of the Italians hired to work on the picture. “The Italians are wonderful at designing things, but they have this natural proclivity for larceny”, said Tom Mankiewicz, the director’s younger son, who like his brother Chris, took time off from college to work on the film. “Once you start saying, “All right, I need 500 Praetorian Guard outfits, I need 600 Nubian slave outfits, I need 10,000 soldier outfits…” this was like an invitation. In addition, there was no one to stay on top of it all. If you wanted to buy some new dinnerware or set of glassware for your personal house, it was the easiest thing in the world to put into the budget for Cleopatra”.

“Later I got to see the studio’s breakdown on the money waste” said Elizabeth, “they had listed 3 million for miscellaneous and $100,000 for paper cups. They said I ate 12 chickens and forty pounds of bacon every day for breakfast. What?”.

Skouras, though the man with the ultimate authority over the production, placed a lot of the blame for the film’s rampant disorganization on Walter Wanger. “You have to know Walter Wanger well”, Skouras later told an interviewer. “He is a fine man but he likes to have lots of people to help him. Off the record. He does not want to work so hard”. Levathes felt that Mankiewicz was a prima donna whose extravagant requests were indulged by Skouras regardless of financial consequences. Walter Wanger complained with some justification that Skouras and Levathes were undermining his authority by circumventing him in favor of Mankiewicz and the department heads, but too often he merely complained and took no action. The surviving actors and crew members remember the producer devolving into a sweet but powerless “greeter” whose most visible duty was to escort visiting European royals around the sets.

As a bout of torrential, London like weather precluded outdoor shooting for much of the fall of ’61 (at a cost of $40,000 to $75,000 for every day rained out), many of the film’s principal actors realized they were going to be in Rome at least through the spring of ’62. So they moved out of the luxurious Grand Hotel and into their own apartments, becoming idle, semi-permanent residents of the city. Given that Fox had to keep the actors on salary the whole time – Hume Cronyn at $5,000 a week, Roddy McDowell at $2,500 a week, Martin Landau at $850 a week, etc., the cost pile ups were tremendous.

At one point in the autumn, Skouras and Levathes approached Burton to see if he’d mind terribly if the movie ended with Caesar’s assassination, thereby cutting out half the plot and roughly 95% of Antony’s part. Burton was very clear, “I’ll sue you until your puce”, he told them.

Given the messy state of affairs, morale in general remained remarkably high on the set. “Everyone was in a very gay way”, said O’Conner. “We knew the picture was going to be O.K., even if it wasn’t going to be one of the greats”. The rushes were impressive enough to prompt hope in some quarters the film was en route to greatness. On Christmas Eve, Fox publicist Jack Brodsky wrote the following to Nathan Weiss, his colleague in New York:

”The first 50 pages of the second act have just come from Mank’s pen and they’re fabulous. Burton and Taylor will set off sparks, and already Fisher is jealous of the lines Burton has”.

Hell Breaks Loose - Rome, Winter 1962

"For the past several days uncontrolled rumors have been growing about Elizabeth and myself. Statements attributed to me have been distorted out of proportion, and a series of conincidences has lent plausibility to a situation which has become damaging to Elizabeth..."

Le scandal

as Richard and Elizabeth later termed their affair, didn't begin until their work together did, in December of January, after Mankiewicz had written enough material for them to start rehearsing the film's second half. “For the first scene, there was no dialogue – we had to just look into each other’s eyes” said Elizabeth. “and that was it – I was another notch.” Richard further endeared himself to Elizabeth by showing up hung over. She had feared that he would lord his talent over her and make fun of her lack of theatrical training, instead, she found herself steadying his trembling hands as he lifted a coffee cup to his lips. “He was probably putting it on,” Elizabeth said. “He knew it would get me.”

As for Eddie Fisher, he had not been having the best of times in Rome. Though he was on the Cleopatra payroll and was trying to learn how to become a movie producer, his prescence wasn’t expected or needed at Cinecittà. “I remember Eddie one day walking onto the set, trying to be funny, and shouting to Mankiewicz, 'O.K., Joe, let’s make this one!'” said Brodsky. “No one reacted and it cast a pall.”

Eddie and I had drifted way apart,” said Elizabeth. “It was only a matter of time for us. The clock was ticking.”

But right through the end of January, the only suspicion that Eddie Fisher held was that Richard Burton was encouraging his wife to drink too much. In his self-described capacity as nurse, Eddie took exception to the Welshman’s exceptional boozing and his zest for life were having on Elizabeth, who had grown weary of her husband’s preference for quietly dining in. “Remember” said someone who worked on the production, “Elizabeth was a very self-indulgent person at that time, a sensualist who’d just been confronted with her own possible death, and was probably rebounding from it by tasting as much of life as possible.”

Several people associated with Cleopatra point out that sensualism and high living were the order of the day in Rome, particularly with so little work for the actors to do. “There was a tremendous sense of being in the right place at the right time,” said Jean Marsh, who played Antony’s Roman wife, Octavia, well before her PBS fame as the creator and star of Upstairs, Downstairs. “Fellini was there, and Italy was the capital of film. And this film was so extravagant, so louche, it affected everyone’s lives. It was a hotbed of romance – Richard and Elizabeth weren’t the only people having an affair.”

Elizabeth and Richard filmed their first scene together on January 22. Walter Wanger happily noted in his diary, “There comes a time during the making of a movie when the actors become the characters they play… That happened today. It was quiet and you could almost feel the electricity between Liz and Burton.”

Some people on the set, including Mankiewicz, already knew there was more going on than just electricity. At one point Richard had walked triumphantly into the men’s makeup trailer and proudly announced to all those present “Gentlemen, I just fucked Elizabeth Taylor in the back of my Cadillac!” Whether or not this boast was for real, it was true that he and Elizabeth were using the apartment of her secretary, Dick Hanley, for their trysts.

On January 26, Mankiewicz summoned Walter Wanger to his room at the Grand Hotel. “I have been sitting on a volcano all alone for too long, and I want to give you some facts you ought to know,” he said. “Liz and Richard are not playing Antony and Cleopatra.”

“Confidentially,” Walter later told Joe Hyams, his collaborator on My Life With Cleopatra, a rush job account of the film’s travails published in 1963, “we figured it might just be a once-over-lightly. That is what Mr. Burton figured, too. I know it. He told me.”Several

first hand accounts support the idea that Richard began his dalliance with Elizabeth with only short-term pleasure in mind. Brodsky recalls the actor’s genuine surprise, as the weeks advanced, to find himself in the midst of both an intense affair and an international incident. “He said to me, ‘It’s like fucking Khrushchev! I’ve had affairs before – how did I know the woman was so fucking famous!’”

Mankiewicz and Walter Wanger harbored hopes in the early going that the situation would simply blow over. But Elizabeth’s notoriety since her grieving-widow days had made her the most hunted tabloid prey in the world. Well before the affair had begun, the Roman gutter press had planted informants in Cinecittà and arranged paparazzi stakeouts at Villa Papa. Word got out fast, even before Eddie Fisher knew anything was going on.

As February arrived, rumors were swirling so madly around Rome - “the whispering gallery of Europe,” as Walter Wanger called it – that Eddie could no longer ignore or brush off the gossip. One night early that month, as he lay in bed beside Elizabeth, he received a heads-up phone call from Bob Abrams, his old army buddy.

Eddie hung up the phone and turned to his wife, “is it true that something is going on between you and Richard Burton?” he asked her.

“Yes,” she said softly.Quietly and in abject defeat Eddie packed and spent the night at Bob Abrams’s place. The following day he returned to Villa Papa, and for about two weeks slept by Elizabeth’s side, hoping the situation would somehow resolve itself. There was never any kind of knock-down-drag-out confrontation. “She just wasn’t ‘there’ anymore” Eddie said in 1991. “She was with him. And I wasn’t ‘there.’ She talked to him once at the studio, in my office, with all kinds of people around. And she was talking love to him on the phone. ‘Oh, dahling, are you alright?’ with this new British accent.”

By mid-February the rumors had gone worldwide and Richard and Elizabeth innuendo was everywhere. The Perry Como Show ran a comic “Cleopatra” sketch in which a slave named Eddie kept getting in Mark Antony’s way. Elizabeth was visibly upset, and the entire production was in a bad way. Mankiewicz, run down from his Herculean work schedule, had become feverishly ill. So had Martin Landau, who had a large part (as Rufio), and who’s illness caused the cancellation of an entire day’s worth of shooting. Leon Shamroy, the cinematographer, a cigar chomping sexagenarian known for his seen-it-all stoicism (he had shot the Fox epics The Robe, The Egyptian, and The King and I, and Gene Tierney’s classic Leave Her To Heaven), collapsed with exhaustion. Forrest ‘Johnny’ Johnston, the film’s production manager, fell gravely ill and finally died in May in Los Angeles.

Morale back home was also low, Pro- and anti-Skouras factions were coming together on the Fox board and rumors swirled of a coming change. “This was where my hair went gray,” said Levathes, “I used to look younger.”

Richard Burton, now contrite, met with Walter Wanger and volunteered to quit the production if that was what was best. Walter counseled against this option, arguing “what would solve the problem is putting an end to any basis for the rumors.”

Meanwhile, Richard’s older brother Ifor, a powerfully built man who functioned as the actor’s bodyguard, used his fists to get the message across. “Ifor beat the shit out of Burton,” says a Cleopatra crew member. “For what he was doing to Sybil. Beat him up so that Richard couldn’t work that next day. He had a black eye and a cut cheek.”

Both Eddie Fisher and Sybil Burton decided it was best to flee the situation. He headed by car for Gstaad, where he and Elizabeth owned a chalet, she left for New York. But before either had gone Eddie paid a visit to the Burton’s villa for a heart-to-heart with Sybil. “I said, ‘You know they’re continuing their affair.’” Eddie later recalled. “And she said ‘He’s had these affairs, and he always comes home to me’. And I said ‘But, they’re still having their affair’. And she went to the studio and they closed production down. That cost them $100,000. And the day I left Rome cost them another $100,000. Elizabeth screamed and carried on. Work stopped that day. They had that in honor of me.”

When Eddie, having driven as far as Florence, called Rome to determine his wife’s whereabouts, he discovered that Elizabeth was in Hanley’s apartment with Richard, who was enraged that the singer had meddled in his marriage to Sybil. Richard too the phone. “You nothing, you spleen,” he said to Eddie. “I’m going to come up there and kill you.”

Instead, Richard summoned the courage to tell Elizabeth their affair was over, and left for a short trip to Paris, where he was playing a small part in Darryl Zanuck’s Normandy epic, The Longest Day. That night Hanley called Walter Wanger to say that Elizabeth was hysterical and would be unable to work the next day. Walter wrote in his diary, “Total rejection came sooner than expected.”

The following day, February 17, Elizabeth was rushed to the Salvator Mundi Hospital. The official explanation was food poisoning. Walter, who cooked up a story about some bad beef she had eaten, had in fact, discovered Elizabeth splayed out on her bed in the Villa Papa, gtoggy from an overdose of Seconal, an Rx sedative. “It wasn’t a suicide attempt” said Elizabeth. “I’m not that kind of person, and Richard despised weakness. It was more hysteria. I needed the rest, I was hysterical and needed to get away.”

Elizabeth recovered quickly, but news of her hospitalization compelled both Eddie and Richard to fly back to Rome, which only fanned the flames of rumor. On February 19, Richard, eager to extinguish these flames, issued a statement addressing the “uncontrolled rumors… about Elizabeth and myself.” The statement to pains to provide reasons why Sybil and Eddie had left town (she was visiting Richard’s sick foster father, he had business matters to attend to), but never outright denied that an affair was going on. It was a crucially unsavvy nondenial denial, and the Fox publicity team became apoplectic. The studio got Richard to disavow the statement and pin the blame for its release on his press agent, but it was too late. Now the papers had a bit of hard evidence on which to hang their ‘affair’ stories. Richard and Elizabeth had been publically ‘outted’.

“It was not a help to the production,” said a crew member, “You know how she got time off for her period? Now she was having three or four periods a month.”

The Whirlwind: Rome, early Spring 1962

"It's true - Elizabeth Taylor has fallen madly in love with Richard Burton. It's the end of the road for Liz and Eddie Fisher...."

In

the aftermath of Elizabeth’s hospitalization, all the damaged parties tried to re-arrange themselves as they had been before. Eddie Fisher threw his wife a 30th birthday party on February 27 and presented her with $10,000 diamond ring and an emerald studded Bulgari mirror. Richard told the press he had no intention of divorcing Sybil. But it was all to no avail – the Richard – Elizabeth affair continued unabated as did the tabloid reporter’s pursuit.

Privately there were cruel scenes between Richard Burton and Eddie Fisher, with Richard visiting Villa Papa and boasting to the latter, “You don’t know how to use her!,” or turning to Elizabeth and saying, with Eddie present, “Who do you love? Who do you love?” Eddie never fought back. Where others saw wimpiness and retreat, Walter Wanger, in recorded conversations with Joe Hyams, his book collaborator, ascribed a kind of nobility to Eddie’s pacifism. “Eddie always took the position that this is an evil man, and he had to stand and protect her when she was misled by this terrible guy,” he said. “He wanted to hold his family together.” Eddie left Rome for good on March 21,1962.

Cleopatra was now about halfway finished, but it still lacked its biggest, most challenging scenes: Cleopatra’s procession into Rome, the arrival of her barge in Tarsus, the battles of Pharsalia, Philippi, Moongate, and Actium. Moreover, there remained several weeks of worth of ‘Antony and Cleopatra’ scenes to be filmed. The fictitious story on-screen and the personal story off-screen fit together so precisely even the actors got confused. “I feel as if I’m intruding,” Mankiewicz said one day as his shouts of “Cut!” went unheeded by Richard and Elizabeth during a love scene. In a less pleasant coincidence, the very day Richard announced to the press he would never leave Sybil was the day Elizabeth had to film the scene in which Cleopatra discovers that Antony has returned to Rome and taken another wife, Octavia. The screenplay called for Cleopatra to enter Antony’s deserted chambers in Alexandria, pick up his dagger, and stab his bed and belongings in a rage. Elizabeth went at it with such enthusiasm that she banged her hand and had to be hospitalized for X-rays. She was unable to work the next day.

The sensational day-to-day developments of Richard & Elizabeth had now become a full time news beat for the tabloids. Martin Landau remembers a night shoot on the island of Ischia involving Richard and Elizabeth where the crew’s spotlights, once turned on, revealed paparazzi bunched up like moths. “Behind us was this cliff, with shrubbery and growth coming out of it,” he said, “and there were 20 photographers hanging off these things, with long lenses. A couple of them fell 30 feet.”

In reality, the affair was, as Elizabeth would note a few years after the fact, “more off, than on.” “We did try to resist,” she has said. “My marriage with Eddie was over, but we didn’t want to do anything to hurt Sybil. She was such a lovely lady.” Elizabeth never would discuss the scenes and machinations that went on between the Fishers and Burtons, calling the subject matter “too personal,” but other observers on the set remember moments when the lovers’ similarly combustible personalities caused near explosions. In the midst of Le Scandal, Richard was also carrying on with the Copacabana dancer he’d been seeing in his Camelot days. One day Elizabeth took exception to his presence on the set, prompting Richard to shove Elizabeth slightly and snarl, “Don’t get my Welsh temper up.” In another instance, Richard showed up for the work wrecked, again with the “Copa cutie,” as she had come to be known on the set. When he finally sobered himself into performing condition, Elizabeth chided “You kept us all waiting.” To which Richard responded, “It’s about time somebody kept you waiting. It’s a real switch.”

Far more so than Elizabeth, Richard was confused, unable to choose between his wife and lover, desperate to have it both ways. Speaking to Kenneth Tynan in Playboy after Cleopatra had wrapped, he futilely tried to defend the Liz-Sybil arrangement with a choice bit of baroque doggerel. “What I have done,” he said “is to move outside the accepted idea of monogamy without investing the other person with anything that makes me feel guilty. So that I remain inviolate, untouched.”

For all its unpleasant side effects, Richard was elated by his new worldwide fame. Kenneth Haigh remembers him “calling me into his room and saying, ‘Look at this! There are about 300 scripts! The offers are piling up everywhere!’” Hugh French, Richard’s Hollywood agent, began boasting that his client now commanded $500,000 a picture. “Maybe I should give Elizabeth Taylor 10 percent,” said Richard.

Alas

the seesaw nature of the affair was not conducive to the efficient completion of what was now routinely described in the papers as a “$20 million dollar picture.” Between his euphoric highs, Richard was drinking heavily on the set. Elizabeth too, became erratic, alternately showing up surprisingly very early to work on scenes with Richard and failing to show up at all. A production document entitled “Elizabeth Taylor Diary” indicates that on March 21, the day Eddie Fisher departed, Elizabeth was dismissed from Cinecittà at 12:35 p.m. after “having difficulty delivering her dialogue.”

The unexpected work stoppages didn’t always bother Mankiewicz, who welcomed the opportunity to catch up on his writing and get some sleep. He was by now a physical ruin, sometimes writing scenes the night before they were to be shot. A stress related skin disorder caused the skin on his hands to crack open, forcing him to wear thin white skinned cutter’s gloves as he wrote the script in longhand. Somehow he kept his sense of humor and balance. When an Italian newspaper alleged that Richard was a “shuffle footed idiot” deployed by the director to cover up the real scandal – that it was Mankiewicz who was really having an affair with Elizabeth – Mankiewicz released a statement declaring, “The real story is that I’m in love with Richard Burton, and Elizabeth Taylor is the cover-up for us.” (The same day, Richard shuffled up to Mankiewicz on the set and said: “Duh, Mr. Mankeawitz, sir, do I have to sleep with her again tonight?”)

Astonishingly, there had been a time, early on in Rome, when the Fox brass had chastised their publicity dept. for not getting Cleopatra enough attention. By April and May of 1962, as le scandal superseded news coverage of the Mercury-Atlas space missions and the U.S. – Soviet tensions that were leading up to the Cuban missile crisis, it was almost impossible to keep up with the whirlwind of headlines about Richard and Elizabeth. Eddie Fisher was briefly hospitalized in New York with exhaustion, and after his release took to opening his nightclub act with the song “Arrivederci, Roma.” A congresswoman from Georgia named Iris Blitch called on the attorney general to block Elizabeth and Richard from re-entering the country, “on grounds of undesirability.” And in April, the Vatican City weekly, L’Osservatore della Domenica, printed a 500-word “open letter”, signed only “X.Y.”, that began “Dear Madam” and went on to say, “Even considering the husband that was finished by a natural solution, there remains three husbands buried with no other motive than a greater love that killed the one before. But if we start using these standards and this sort of competition between the first, second, third, and the hundredth love, where are we all going to end up? Right where you will finish – in an erotic vagrancy … without end or without a safe port.”

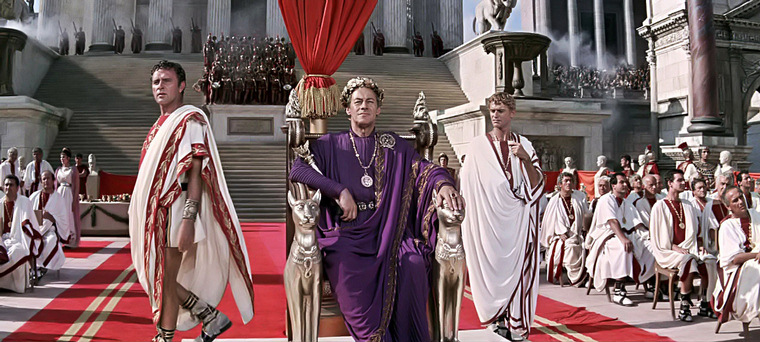

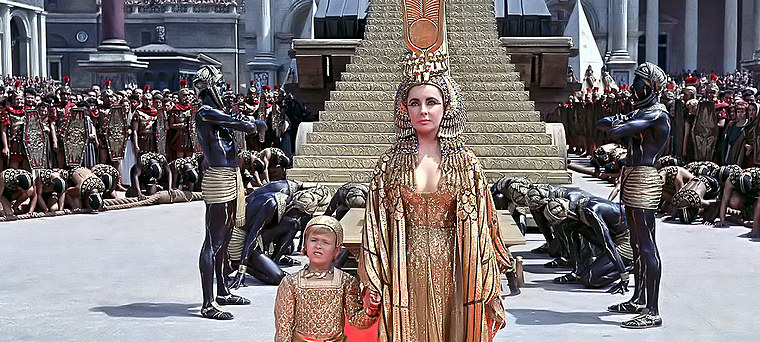

The complicity of the Catholic Church in the sport of Liz-bashing undid Elizabeth’s nerves at the worst possible moment for the production. She was due, at last, to film Cleopatra’s entrance into Rome, the centerpiece of the entire picture. The premise of the sequence, commonly known as the procession, is that Cleopatra, having borne a son to Caesar in Egypt, must now go to her lover’s home turf to present herself to the Roman public. If they accept her, then her dream of a globe-straddling Egyptian-Roman empire is realized; if they boo and hiss, she is finished. Mankiewicz, hewing to Plurarch, addressed the situation precisely as Cleopatra did: by devising the most lavish, eyeball-popping spectacle he could think of, a NASA-budgeted half-time show.

As Caesar, Antony and the senators watch, agog, from the Forum’s reviewing stand, a seemingly endless parade of exotica would stream through the Arch of Titus: fanfaring trumpets, charioteers, scantily clad dancing girls with streamers, an old hag who changes magically into a young girl, dwarfs tossing sweets from atop painted donkeys, comely young women tossing gold coins from atop painted elephants, painted Watusi warriors, dancers shooting plumes of colored smoke into the air, a pyramid that bursts open to release thousands of doves, prancing Arabian horses, and, for the finale, a two ton, three story high, black sphinx drawn by 300 Nubian slaves, upon which would sit Cleopatra and her boy, Caesarion, both shinning in gold raiment.

Originally, the procession was to be one of the first things shot, in October, but bad weather and inadequate preparation made a hash of that plan, forcing Fox to pay out money to various dancers, acrobats, and circus-animal trainers to ensure their availability through the spring. (Furthermore, the original elephants that had been hired proved too unruly and destructive, one of them running amuck on the Cinecittà soundstages and pulling up stakes; the elephants owner, Ennio Togni, later attempted to sue Fox for slander when word got out that his pachyderms had been “fired.” Said a disbelieving Skouras, “How do you slander an elephant?”)

Six thousand extras had been hired to cheer the queen’s entrance and adlib reactions of “Cleopatra!, Cleopatra!,” but Elizabeth, mindful of their Roman Catholicism and the Vatican’s recent condemnation, feared an impromptu stoning. Comforted by Richard and Mankiewicz, she summoned up the courage to be hoisted atop the sphinx. When the cameras started rolling, she assumed a facial expression of blank hauteur and felt the sphinx rolling through the arch. “Oh my God,” she thought “here it comes.”

But the Roman extras neither booed nor (for the most part) shouted “Cleopatra! Cleopatra!” Instead they cheered and yelled, “Leez!, Leez! Baci! Baci!,” while blowing kisses her way.

- Click Pic above to see "The Procession" on Utube -

The Homestretch: Spring-Summer 1962

“Mr. Skouras faces the future with courage, determination …and terror.”

Groucho Marx speaking at a testimonial dinner held in honor of Spyros Skouras at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, April 12,1962.

In the spring of ’62, Skouras saw the writing on the wall. He knew that his reign as Fox president wasn’t going to last much longer. By May he was stricken with prostate trouble, and when he arrived in Rome on May 8 to screen a five-hour rough cut of Cleopatra-to-date, he had been fitted with a temporary catheter and was heavily sedated – and fell asleep several times during the screening. Satisfied nevertheless with what he saw, he began to push to finish the film as quickly as possible.

The month had begun with Elizabeth indisposed on account of what Walter Wanger described as “the most serious situation to date.” On April 21, Richard and Elizabeth, without forewarning any members of the production, left Rome to spend the Easter weekend at Porto Santo Stefano, a coastal resort town a hundred miles to the north. Unprotected by handlers and publicists, they were followed the entire time by a swarm of reporters and paparazzi, and the following day newspapers around the world ran pictorial stories of their “tryst at seaside.”

“It was like hell”, said Elizabeth. “There was no place to hide, not in this tiny cottage we had rented. When we were driving somewhere, they ran us into a ditch by jumping in front of the car. It was either Richard hits them or he swerves over, so we swerved over.”

One of the Porto Santo Stefano “tryst” stories appeared in the London Times, which infuriated Sybil Burton, who was at home in England with the Burtons’ two small daughters, Kate and Jessica. Sybil had studiously ignored the London tabloids, but to have the Taylor-Burton affair splashed across the Times was the last straw. She went to Rome on April 23 to await her husband’s return. Walter Wanger, fearing a public scene, detained her at the Grand Hotel for as long as he could.

In the meantime, Elizabeth returned abruptly and solo from Porto Santo Stefano, and was rushed, for the second time in four months, to the Salvator Mundi Hospital. The following day’s papers carried news of a “violent quarrel” that had prompted Elizabeth to walk out on Richard as he stood, smoldering, on the porch of the stucco bungalow they were staying in. “Richard told her to go and get rid of herself, and she tried to,” Walter Wanger said confidentially. “This was the one time she really took an overdose and she was really in danger.” Elizabeth again denies that suicide was her intent, saying that, as had been the case in February, she needed some respite.

The hospitalization could be explained away with the old standby “exhaustion” and “food poisoning,” but the reason she didn’t work again until May 7, was that she had a black eye and facial bruises, could not be so easily addressed. Skouras, in a letter to Darryl Zanuck several months later, matter-of-factly referred to “the beating Richard gave her in Santo Stefano. She got two black eyes, her nose was out of shape, and it took 22 days for her to recover enough in order to resume filming.” Elizabeth maintained the truth was what the press was told – that the bruises were incurred during the ride back from Porto Stefano. “I was sleeping in the backseat of the car,” she said, and the driver went around a curve, and I bumped my nose on the ashtray.”

O

nce Elizabeth’s bruises healed, she went back to work. But, more bad luck followed. The winds came up on some of the days the extras and dancers had been convened to continue work on the procession, canceling shooting at a cost of $250,000. A successfully completed scene that required Antony to slap Cleopatra to the ground – a loaded proposition made more so by the fact that Elizabeth had a bad back – was erased when the film was damaged in transit back to the United States; June retakes would be necessary. Then, on May 28, word slipped out to Levathes that Elizabeth had filmed Cleopatra’s death scene, in which she commits suicide by letting an asp bite her hand. The death scene was, in the eyes of Fox’s impatient executives, the one sequence the film could absolutely not do without. Knowing it existed, Levathes headed for Rome to shut down the picture.

On June 1, Walter Wanger met with Levathes and learned that, effective the following day, he was going to be taken off salary and expenses. This was, in every sense a quasi-firing, in that no one discouraged from continuing to work on the film. So continue, he did, contesting with Mankiewicz, the New York office’s demands that Elizabeth’s last day be June 9, that the battle of Pharsalia sequence be cancelled, and that all photography be completed by June 30. (A week later, back iin the U.S., Levathes fired Marilyn Monroe from her abortive final film Something’s Gotta Give. A Fox spokesman said, “No one can afford Monroe and Taylor.”)

In haste, the Cleopatra production moved the Italian island of Ischia, which was standing in for both Actium, the ancient Greek town near whose shores Octavian defeated Antony, and Tarsus, the Turkish port of the Roman Empire where Cleopatra made her second great entrance, aboard a barge. (The barge, complete with gilded stern and Dacron purple sails flown in from California, cost $277,000.)

It was off Ischia that a paparazzo named Marcello Geppetti took the photograph that most enduringly represents the Taylor-Burton affair: a shot of Richard planting a kiss on a smiling Elizabeth as both sun themselves in bathing suits on the deck of an anchored boat (See the photos section Click Here).

Elizabeth completed a successful take of Cleopatra’s arrival aboard her barge on June 23. By studio decree, it was her last day on the picture – 272 days after Mankiewicz had begun at Cinecittà, 632 days after Mamoulian had commenced shooting at Pinewood Studios.

Battle-sequence work in Egypt would keep Mankiewicz busy through July, and battles with Fox occupied him in the weeks prior. While still on Ischia, the director learned that Fox was killing yet another crucial sequence, the battle of Philippi. Mankiewicz was enraged, having planned for the Philippi conflict to open the second half. On June 29, he sent a strongly worded telegram to Skouras and the Fox brass:

WITHOUT PHARSALIA IN MY OPINION OPENING OF FILM AND FOLLOWING SEQUENCES SEVERELY DAMAGED STOP BUT WITHOUT PHILIPPI THERE IS LITERALLY NO OPENING FOR SECOND HALF SINCE INTERIOR TENT SCENES ALREADY SHOT SIMPLY CANNOT BE INTELLIGENTLY PUT TOGETHER STOP … WITH MUTUAL APPRECIATION OF RESPONSIBILITIES AND SUGGESTING THAT MINE TOWARD THE STOCKHOLDERS IS NO LESS THAN YOURS I SUGGEST YOU REPLACE ME SOONEST POSSIBLE WITH SOMEONE LESS CRITICAL OF YOUR DIRECTIVES AND LESS DEDICATED TO THE EVENTUAL SUCCESS OF CLEOPATRA.

Fox placated Mankiewicz by allowing Pharsalia to be partially reconstituted via two days’ worth of hasty shooting in some craggy Italian hills – and then Cleopatra moved on to Egypt for additional battle work.

The Egypt trip, from July 15 to July 24, was the by-now-customary fiasco, marred by delays, poor sanitary conditions, a threatened strike by the locally hired extras, and government wiretaps on the telephones of Jewish cast and crew members: adding injury to insult, there was the further deterioration of Mankiewicz’s physical condition – he now required daily B12 shots to keep going, and one shot hit his sciatic nerve, rendering him barely able to walk.

Principal photography was now complete. But Mankiewicz would have more to contend with in the film’s lengthy postproduction phase: a new Fox regime. Back on June 26, under pressure, Skouras had announced his resignation as president, effective September 20.

Enter the Mustache: 1962-63

IT LOOKS LIKE MUSTACHE WITH ZEUS AS PLANKHEAD

Cable sent from Jack Brodsky (Fox New York Office) to Nathan Weiss (Fox Rome Office), July 6 1962

M

ustache was Darryl Zanuck. “Zeus” was Skouras. Upon Skouras’s resignation, Zanuck, whose family was still the single largest shareholder of Fox stock, made a play to take control of the faltering company he had co-founded in 1933. By outmaneuvering the various board factions and their designees for president, he engineered a coup that by summertime had installed him as president and relegated Skouras to a largely ceremonial chairman-of-the-board position (ergo, “Zeus as plankhead”).

Zanuck surveyed the state of affairs like a police chief arriving at a morbid crime scene - move along pal, show’s over. He shut down virtually all Fox production except Cleopatra, dismissed most of the studio’s employees and executives, lowered the thermostats, shuttered most of the buildings on the shrunken back lot, and replaced Levathes with his own son, producer Richard Zanuck.

Mankiewicz and Darryl Zanuck had a complex love-hate relationship that more often tipped toward the latter. But the director was pleased to know there was now a decisive man at the top, and someone who knew the ins and outs of picture making to boot. “When I finished a screenplay, the first person I wanted to read it was Darryl,” Mankiewicz said in 1982, recalling the days when Zanuck was Fox’s chief of production. It was Zanuck who resolved one of Mickiewicz’s biggest writerly delimmas – how to pare down an overlong screenplay entitled A Letter To Four Wives - by suggesting that Mankiewicz eliminate one of the wives.

Back in Los Angeles, Mankiewicz and his editor, Dorothy Spencer, prepared a rough cut of Cleopatra that ran five hours and twenty minutes and reflected his desire to present Cleopatra in two concurrently released parts, with separate tickets required for each: Caesar and Cleopatra, followed by Antony and Cleopatra. Fox had long been against the idea, because of the exhibition logistics involved and because no one was interested in seeing Elizabeth make love to Rex Harrison.

Mankiewicz made a date with Zanuck to screen the film on October 13 in Paris, where the new Fox president lived (and continued to work, even though he was running an American studio). As this date approached, Walter Wanger sent Zanuck a series of obsequious letters and telegrams, begging to be fully reinstated as producer:

I BESEECH YOU, DARRYL … NOT TO AGGRAVATE THIS SITUATION AND FURTHER DAMAGE MY STATUS AS PRODUCER OF CLEOPATRA BY NOT BRINGING ME TO PARIS … I APPEAL TO YOU AS A MAN NOT TO DO THIS TO ME

Zanuck’s cold shoulder reply was that Walter Wanger was welcome to come along provided he paid his own way.

The October 13 screening did not go particularly well. Zanuck said little to Mankiewicz as the lights went up except “If any woman behaved toward me the way Cleopatra treated Antony, I would cut her balls off.”

Mankiewicz grew nervous when a week passed without him hearing anything further. On October 20, he sent a letter to Zanuck requesting an “honest and unequivocal statement of where I stand in relation to Cleopatra.”

On October 21, he got his statement. “On completion of the dubbing, your official services will be terminated,” Zanuck wrote. “If you are available and willing, I will call upon you to screen the re-edited version of the film.” Elsewhere in the letter, which ran to nine single spaced pages, Zanuck described the existing battle sequences as “awkward and amateurish … second rate film making” with a “B-picture” look; said that the film “over emphasized in some places the Esquire-type of sex”; described Walter as “impotent”; contrasted Mankiewicz’s handling of Cleopatra unfavorably with his own handling of The Longest Day; and alleged, “You were not the official producer, yet in the history of motion pictures no one man has ever been given such authority. The records show that you made every single decision and that your word was law.”

A few days later, Zanuck released the following statement to the press: “In exchange for top compensation and a considerable expense account, Mr. Joseph Mankiewicz has for two years spent his time, talent, and $35,000,000 of 20th Century Fox shareholder’s money to direct and complete the first cut of the film Cleopatra. He has earned a well-deserved rest.”

In response, the director told the press, “I made the first cut, but after that, it’s the studio’s property. They could cut it up into banjo picks if they want.”

Privately, Mankiewicz sent Zanuck yet another letter that painstakingly refuted every charge made against him in the October 21 correspondence: “I am, I suppose, an old whore on this beat, Darryl, and it takes quite a bit to shock me … but never could I imagine the phantasmagoria of frantic lies and frenzied phony buck-passing that you report in your letter!”

By December, however, the two men’s temperatures had cooled, and they recognized that their cooperation was necessary to get Cleopatra into a releasable form. Zanuck conceded to Mankiewicz that the previous regimes cutbacks on Pharsalia and Philippi had been a mistake, and so, in February 1963 – at a cost of $2 million - Cleopatra’s company of soldiers was reconvened in Almeria, Spain, to do battle. Further bits and pieces were shot in – irony of ironies – Pinewood Studios in England, where the whole mess had begun with Mamoulian 29 months earlier.

When the reshoots were done, Mankiewicz, with Zanuck looking over his shoulder, edited Cleopatra down to its 243-minute premier length. Though they were publically allies again, the director was unhappy with this version and still thought Zanuck had done him a disservice by not allowing Cleopatra to be shown in two parts. When Mankiewicz was asked to participate in the fluffy NBC tribute program called The World of Darryl Zanuck, he said he’d do it only if they retitled it to Stop the World of Darryl Zanuck.

Nevertheless, Cleopatra, at last, was done.CODA: 1963

“She is an entirely physical creature, no depth of emotion apparent in her kohlladen eyes, no modulation of her voice that too often rises to fishwife levels. Out of royal regalia, en negligee or au natural, she gives the impression that she is really carrying on in one of Miami Beach’s more exotic resorts than inhabiting a palace in ancient Alexandria.”

Judith Crist, evaluating Elizabeth’s performance in her review of Cleopatra for the New York Herald tribune, June 13, 1963

C

leopatra opened at the Rivoli Theater to mixed reviews, Crist’s being the most damning, Bosley Crowther’s, in The New York Times, being the most enthusiastic (“a surpassing entertainment, one of the great epic films of our day”). A viewing unprejudiced by temporal context reveals the movie to be mediocre-to-good, a tribute to Mankiewicz’s salvaging abilities and the fact that, for all the waste, you do see a lot of the money up on the screen – the movie looks handsome and expensive in an old fashioned, 2,000 artisans at work way, as opposed to the more contemporary, post produced-in-the-computer-lab way. The procession sequence is as mind-boggling as it’s supposed to be.

Elizabeth’s Cleopatra comes off as an imperious harridan, a seething Imelda, but she’s actually effective – you believe her dream of empire. Still, you can’t help but notice the inconsistency of her physical appearance throughout the film, a consequence of the events and upheavels she was enduring. At times, she's skinny and youthful; other times, she’s fleshy but ravishing; still other times, damned if she isn’t Mrs John Warner foretold. The male leads’ fortunes are more contingent upon the circumstances under which Mankiewicz wrote their parts. Whereas Rex Harrison gets all the good lines, Richard looks ludicrous and spends most of his screen time shouting, flaring his nostrils, and huffing around Alexandria in a strangely tiny mini-toga (he shows more leg than Cyd Charisse). Not that poor writing was entirely to blame – Mankiewicz’s completed screenplay contains nuanced, character-building Antony scenes that never should have ended up on the cutting room floor.

Business at the Rivoli was good, and the movie sold out for the next four months; Skouras, his exhibitor’s skills coming to the fore, had shrewdly arranged a deal whereby Fox collected $1.2 million in advance guarantees from the theater before a single ticket had been sold. Applying this strategy worldwide, he collected $20 million in pre-release grosses.

The movie was never the runaway hit Walter Wanger had dreamed of, but a year after its release it was one of the top 10 grossers of all time, and in 1966, when Fox sold the television broadcast rights to ABC for $5 million, Cleopatra passed the break even mark. The studio had by then rehabilited itself - The Sound Of Music, which had come out a year earlier and cost $8 million to make, was an unexpected mega-hit, grossing more than $100 million.

But, the travails of Cleopatra did not end at the Rivoli. Subsequent to the New York premier, Fox chopped the film down further. For the Washington D.C. and London premiers, a three hour forty-seven minute version was shown. When the film went into wide release, it was even shorter, running at three hours and twelve minutes. If big-city moviegoers were gypped out of seeing Mankiewicz’s vision realized, most Americans were gypped out of seeing a comprehensible film.

With the support of the Mankiewicz family and Fox’s former studio chief (1994-2000) Bill Mechanic, archivists have been laboring a six hour “Director’s Cut” of the film that would do better justice to Richard’s part, and the film as a whole, than the 243-minute ‘opening night’ version distributed on video. The Cleopatra Mankiewicz envisioned has been scattered to the winds. Some missing footage has turned up in the hands of private collectors. Other bits and pieces have been discovered, uncatalogued and amile deep in the earth, in an underground storage facility in Kansas. Further bits have turned up in even stranger places: Richard Green and Geoffrey Sharp, two eagle eyed Cleopatra enthusiasts in London who were assisting Fox in the restoration efforts, noticed that Charlton Heston used chinks of excised Mankiewicz footage to flesh out his 1972 low-budget vanity production of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.

The saga of Cleopatra dragged on unhappily for several more years, with a great deal of bad blood, and threats, and lawsuits. Richard, Elizabeth and Eddie Fisher sued Fox for their proper shares of the grosses. Fox sued Elizabeth and Richard for breach of contract, specifically citing Elizabeth for, among other things, “suffering herself to be held up to scorn, ridicule, and unfavorable publicity as a result of her conduct and deportment.” Walter Wanger sued Spyros Skouras, Darryl Zanuck, and Fox for breach of contract. Fox sued Walter Wanger right back on the same grounds. Skouras contemplated a libel suit against Walter Wanger for the way he was portrayed in the 1963 book My Life With Cleopatra, and another suit against the publicists Brodsky and Weiss for the way he came across in their book in 1963, The Cleopatra Papers. By the late 60s, after several rounds of depositions and negotiations, all of these various actions were eventually resolved.

The matter of the Fishers and the Burtons also stretched well beyond Cleopatra’s production life span. When principal filming was completed, Richard returned once more to his wife, and Elizabeth, for the first time in years, had no man in her life. By early 1963 the two had reunited to do another movie, The V.I.P.s, a London-based production that gave them an excuse to take adjacent suites in the Dorchester Hotel. Sybil Burton filed for divorce that December, Eddie Fisher, after months of ugly exchanges with Elizabeth over the division of property, finally gave up the ghost on March 5, 1964, when he failed to contest her petition for a Mexican divorce.

Richard was playing Hamlet in Toronto when Elizabeth’s divorce was finalized; she was with him. They married in Montreal on March 15. The following night, Richard was back in Toronto playing the Dane. After taking his curtain call, he presented his wife to the audience and declaimed, to the audience’s delight, “I would just like to quote from the play – Act III, Scene I: ‘We will have no more marriages.’”

THE PHOTOs

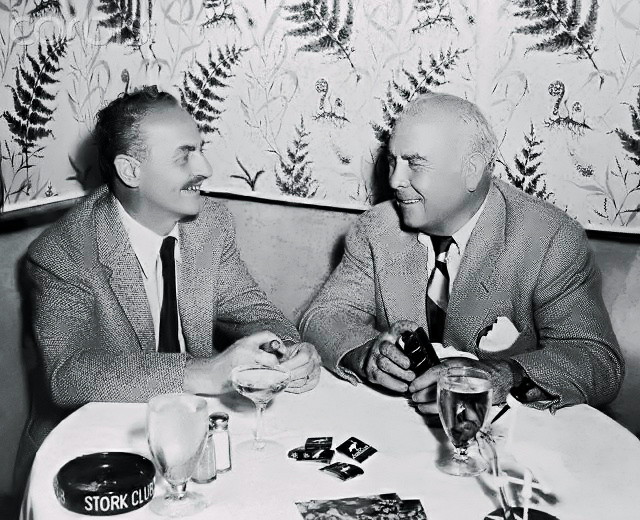

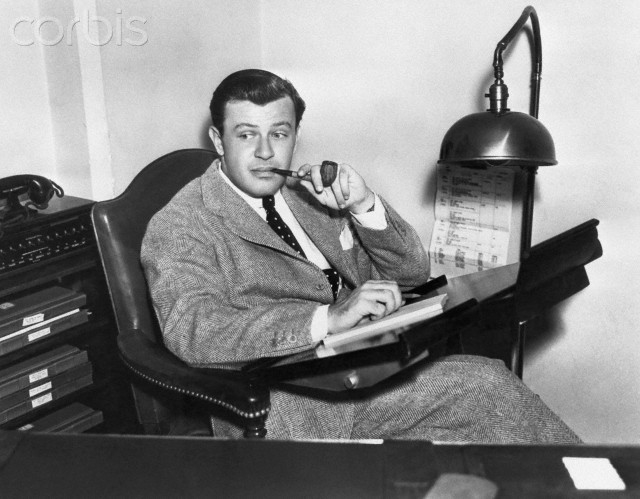

Walter Wanger before he shot Jennings Lang in the crotch.Click Pic above to Enlarge. To read about it, Click here.

Ouch !

ABOVE: Jennings Lang (right) MCA talent Agent representing actress Joan Bennett (center)

who was then the wife of Walter Wanger. To read about it, Click here.